This presentation may seem like a departure from the main theme of evaluation education, yet identifying and understanding the misconceptions and myths that pervade evaluation is key to developing a fine respect for science, building confidence and excellence in spirits evaluation, and changing the gross misinformation accepted as truth. Gaining useful knowledge involves looking past superficial ‘quickie” explanations to find true reasons certain things happen. Deeper investigation brings common sense into the picture and improves understanding.

How are myths created?:

- Hasty explanations and suppositions when the science is not understood create myths

- Myths are created from misunderstanding of events or their outcomes

- Myths are born in marketing departments along with marketing science (not the same as real science)

- Myths become memes the longer they exist unchallenged.

How can we correct the misinformation? The spirits industries of the USA, Scotland, the UK, and Ireland would do well to examine the new set of priorities held by future drinkers. Younger entry-level spirits drinkers categorically reject marketing nonsense, have a strong sense of community, and readily embrace applied science. The spirits industry has a rare opportunity to significantly improve industry credibility among new, young consumers. Science connects with consumers on a higher level, and if applied properly, can enhance consumer enjoyment, improve quality, boost sales and profits, and build loyalty.

Most industry brand ambassadors fail in their role as educators because they tirelessly repeat myths and mistaken assumptions until they are regarded as truth without question. Training brand ambassadors properly and adopting a truly scientific approach to spirits education will dispel misconceptions and encourage discoveries. The industry wins, the consumer wins, competition becomes pure, marketing comes to its senses, and the quality bar is raised throughout the industry.

Learning the truth and correcting others when they misspeak is a good way to correct misinformation. Read and understand the right things by fact-checking. Journalists tend to build in untrue but romantic explanations of how things happen. Intelligent, corrective responses to articles are a good way to get them to fact-check before they publish.

Here are a few more myths currently held by drinkers that need to be corrected:

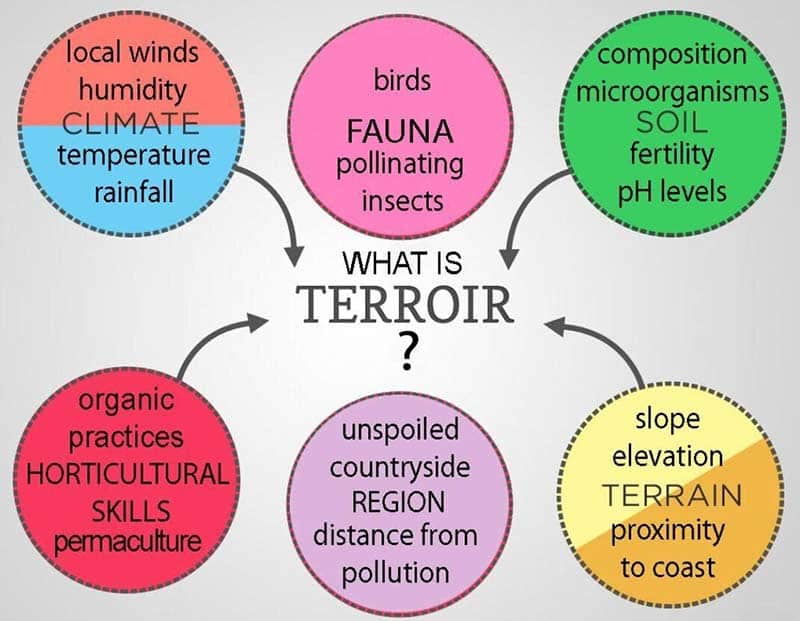

Myth #1 – Terroir in Spirits: Recently, there have been frequent appearances of articles proclaiming the notion of terroir in spirits, particularly scotch. The definition of terroir:

- (Wikipedia) Terroir (/tɛˈrwɑːr/, French: [tɛʁwaʁ]; from terre, “land”) is a French term used to describe the environmental factors that affect a crop’s phenotype, including unique environment contexts, farming practices, and a crop’s specific growth habitat. Collectively, these contextual characteristics are said to have a character; terroir also refers to this character.

- (Merriam-Webster) ter·roir | \ ˌter-ˈwär \ terroir: the combination of factors including soil, climate, and sunlight that gives wine grapes their distinctive character

- (Dictionary.com) terroir [ter-wahr: French ter-war] the environmental conditions, especially soil and climate, in which grapes are grown and that give a wine its unique flavor and aroma

- (UK Dictionary) terroir Pronunciation /tɛrˈwɑː/ /tɛrwar/ the complete natural environment in which a particular wine is produced, including factors such as the soil, topography, and climate. ‘Literal-minded fundamentalists love to call terroir the soil and climate of a specific vineyard, but in truth, it’s about husbandry, about sensitivity to place and its careful management so that the best of things can be delivered of it.’

Terroir is generally associated with wine and has been in the spoken and written word for decades. Upon closer scientific examination the definitions are vague, and more questions than answers appear. Many flavors and aromas occur in wines which are explained away by dumping them into the category of terroir, the convenient catch-all for non-scientific wine lovers who smell funky, aromas, concluding that they must be terroir because “…grapes just don’t smell or taste like that.” Everything which has no name to the evaluator is called terroir. Sloppy “science,” and sloppy evaluation leads to misinformation.

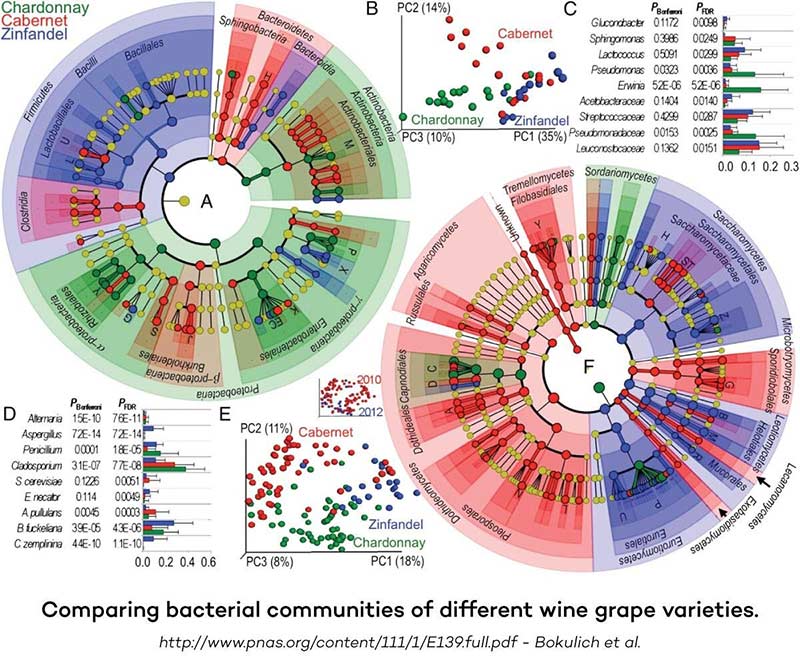

The diagram below is a good representation of the character of terroir.

Many terroir-associated aromas arise during fermentation and from the yeast, and many more are added from oak barrels. Some may come from stems and leaves inadvertently left in the crush and fermented along with the fruit. Some may come from the bacteria found in the soil in particular regions or associated with a specific grape varietal. Conversations of terroir seldom exist in white wines, particularly those processed in stainless steel. Terroir is also said to be influenced by human factors of traditional growing and vinting processes within a region. Terroir generally seems to come into the evaluator’s conversations more often when discussing oak barrel-aged red wines, where bacterial and fungal aromas grow during the aging process, perhaps leading to the confusion of barrel-associated aromas with regional terroir aromas and flavors.

Suspecting barrels are the growing place for many aromas ascribed to terroir in wine, some winemakers purify their barrels with a sulfur match (an old Dutch method) to consume the oxygen and slow microbial decomposition. This process is still common in Bordeaux. Most add sulfur dioxide to the macerated grapes or the fermenting must to kill natural molds and bacteria transported from the vineyard, and has the side effect of aiding extraction. Sulfites also may be added during racking or blending. Low fermentation temperatures are conducive to bacterial and fungal (spore) growth. Adding sulfites doesn’t correct all aromas and odors, nor does it affect the minerality of the soil which may come through in the wine, yet its application could affect aromas typically ascribed to terroir. The chart below, is indicative of the ongoing research of identifying bacteria as specific to terroir. Much is still unknown.

Cool-produced white wine is generally fermented under 16°C, and peak red wine fermentation is just over 29°C. However, distillation begins at 78°C, and average is around 93°C. Complete microbicidal sterilization occurs in the 160°C-190°C range. Fungi and yeast are killed in 71°C to 75°C, penicillium is killed at 55°C. Many aromas in wine commonly ascribed to terroir are killed at distillation temperatures.

The case for no terroir in spirits: The real killer is the ethanol. Hand sanitizers are used at room temperatures and made from both ethanol and methanol because they break down cell membranes, the bacteria die, and dissolve quickly (amphiphilic). If the yield of ethanol from a distillation is around 90+ % its concentration is more than adequate to kill bacteria (CDC says 60%, some now say 90% ethanol is necessary to kill Covid completely). Most of what is commonly described as terroir in wine cannot exist in spirits unless it is added after initial distillation (not terroir, because it did not come from the land or climate but perhaps in the barrel of an aged spirit).

The question that must be asked, is “How can we discuss or discover a particular terroir in spirits if we have no idea where the grain was grown?” Unlike wine-makers, the geographic source of spirits grains cannot be precisely known, as most distillers do not grow their grain and buy from various suppliers, and do not have the advantage of tracking the climate and soil contributions peculiar to a fixed location, as does a specific vineyard belonging to the winemaker.

If terroir in spirits is not understood, recognizable, repeatable, and trackable from its region of origin, what good is it? Is it really terroir? What could be the terroir characteristics of vodka? Would we know the exact growing area of the grain or potato (or other source)? Could we say that it was characteristic (if we could detect it repeatedly) of all grains from that region? Will we sit back someday and say with confidence, “I detect the aromas in this vodka to be highly characteristic of potatoes grown on the north side of hill #71 in the Idaho russet potato appellation?” Many more questions arise about the definition of terroir than about description.

Terroir in spirits is pushing the envelope of believability and rationale and has not yet been substantiated by science. Terroir has not been definable or detectable in the final distilled products of plums (slivovitz), tangerines (liqueur), lemons(limoncello), agave(tequila), sugar cane (rum), and these sources are chemically more complex than grain, so why would wheat or corn have terroir, what exactly is it, and how would you track it to a specific area with a specific soil, climate, water, etc.? Scientific proof could change that, but for now, fuggedaboudit.

Takeaway: True terroir exists in wine in the instances that aromas can be traced directly to the soil, practice, or particular climate cycles. Counter to its definition, among amateur tasters, terroir has come to mean any aroma or flavor that can’t be explained. Many more aromas are relegated to “terroir” by those who steadfastly ignore science. The mystique of terroir is misused by marketers who love to embellish and link vineyards to flavor and aromas. Perhaps spirits “experts” love to have another tool to add excitement to their prose. At best, terroir as referred to in wine is an ill-defined, catch-all category, and terroir in spirits cannot be proven to be more than a fantasy. Look somewhere else for a descriptor of those aromas and flavors whose source hasn’t yet been discovered. A better definition of the exact aromas, flavors, and chemical compounds ascribed to the term terroir is necessary for accurate evaluation.

Myth #2 – Salty sea air tastes of island scotches: Many tasters of scotch swear by the salty taste of scotches which were aged close to the coast of Islay, Jura, Skye, and Arran, crediting the salty sea air and atmosphere for a salty taste characteristic. Marketing again triumphs as science fails to immediately step in and debunk misleading information. These whisk(e)ys are barrel-aged near the coast, and there may be a slight amount of salt in the air, but how did it ever get in the barrel? The answer is creative, romantic imagination to support marketing. The barrel is sealed. If salt could get in, scotch could get out, leaking or quickly evaporating (some do, and there is an air interchange, but the salt stays outside the barrel. Googling “sea air in scotch” one finds all the pictures of scotch which has been reviewed by the romantic evaluators, but no scientific evidence or diagrams of how this occurs. Plenty of reviews exist with distillers who note the characteristic in their scotch, but not a single piece of scientific evidence can be found that verifies its existence. Then there is the smell of the salt. What is that like? We know it as a taste without a smell. Taste receptors are on the tongue.

The scientific approach: If the barrel is loosely constructed, the air could get in, but the scotch would leak or evaporate quickly. If the barrel is tightly constructed, the air would slowly permeate the barrel as it does the cork in a wine bottle, but the probability of salt coming along through the membranes or tightly swollen stave seams is unlikely if not impossible. The salt crystals would precipitate onto the outer surface of the wood, around the seams, leaving a tiny white line at every seam. There is a better chance that microbial bacteria would permeate a seam than salt crystals which remain after wet salty water dries up. The salt is in solution and carried around by the water moisture in the air, not the air itself.

Perhaps if the scotch was made with salty water, the barrel was inadvertently washed with saline water, or salt was added to the barrel, the story would be different, but not due to distillation and aging near the coast as a primary cause. One other possibility is if the mash is exposed to open air during the fermentation process, but then, the question is “Can salt from the air have survived the distillation process in high enough concentration to be detectable?” Research has uncovered nothing to validate that theory.

Seaspray (spume) exists as a natural product of the violent churning of waves and wind. Called SSA (sea salt aerosol) it is responsible for a significant degree of heat and moisture exchange between the ocean and the atmosphere. Seaspray bubbles burst at the interface of water and air, rising from crashing waves, commonly leaving light salt deposits on the pier, docks, and buildings close to the wave action and exposed to the weather, but the notion ends there.

Salinity has been detected in wines made from grapes grown near the coast, and there could be a coating of sea spray on harvested grapes which would add salinity to the fermenting must. What about the barley in scotch? Some barley is grown on Islay, but it is not the only barley used in Islay scotch, so perhaps some of the barley could have salt deposits, but could the salt survive the distillation temperatures to be detectable on the tongue?

During fierce and prolonged storm conditions, salt spray can travel as much as 25km within the atmospheric boundary layer, but jet droplets and spumes from normal wave action travel only about 20cm from the water surface and with the help of storm velocity winds can travel a horizontal distance of around a hundred feet or so. Storm seasons occur in the fall and winter (cool or transitioning temperatures) and the barrel seams are tight enough to prevent leakage. During the summer, sea spray consists of 60-90% DOC (dissolved organic carbon), and an additional percentage of dead algal cells and the product of algae blooms, not salt. During winter storms, the salt content is much higher than DOCs.

Subsequent rain accompanying most storms washes down the salts and DOCs to the ground. Inside the sheltered storage facilities, including those built in the path of winds from the sea, atmosphere salt levels are much lower than those just outside, and the salt still has to get inside the barrel before it settles out of the atmosphere. Again, detectable salt content in a whisky could come from using brackish water or washing a barrel with salt water rather than from the effect of salt spray, but that is not nearly so romantic, idyllic, or picturesque.

There is no proof that salt can travel through the barrel staves or their seams to combine with the spirit. Additionally, we hear nothing from the experts’ blind tastings which verify the taste of algae, dead fish or seaweed in scotch distilled in coastal areas. If the salt comes from the salty peat burned to provide heat for malting the barley, how did it get to the barley? Did crystals of salt from the barley come up through the holes in the malting floor, carried up by rising heat, as the phenolic, smoky flavors did? Seems unlikely, since salt is easily transferred in moisture, but the heat of flames dries up the moisture entirely. Atmosphere or heat alone will not transfer the very smallest salt crystals. If there was any salt, it may be detected in the ashes of the peat. Most charts that describe the characteristics of different scotch whisky regions speak to the peatiness of these coastal whiskies, yet do not mention saltiness as a flavor characteristic, either taste or smell.

In the unique case of Jefferson’s Ocean, the distiller has clarified the purpose that barrels are taken to sea. This process has nothing to do with absorbing salt from the sea air. Barrels in the holds of large ships, protected from sea foam are actually at a nearly constant temperature, but continued sloshing of the liquid in the barrel due to ocean wave action on the ship aids in hastening aging, with constant rewetting of the oak in the airspace of the barrel and continuous remixing of oak sugars throughout the barrel’s liquid contents. Shipboard movement frequency is far quicker than stationary aging.

We are confident that the mash bill of Jefferson’s Ocean, although kept secret, is high in corn and rye (it is a bourbon, 51% minimum corn, and the presence of rye is taste detectable) but the probability that these grains were grown close enough to the seacoast to pick up brine/foam deposits is highly unlikely. Further isolation in the hold, protection against extreme temperatures, and temperature variability is important to the expansion and contraction of the barrels to bring more oak barrel compounds into the spirit. Temperature variance measured in the holds of wine-carrying ships to trace heating, shows definitively that temperatures change very little (less than + 3 degrees C in the ship’s hold on normal voyages from Europe to the east coast USA, and that dock exposure time, sitting in hot containers in the direct sun, are the absolute worst conditions and a major cause of destroying wines in hot seasons before reaching the store shelves.

One story published in Beverage Dynamics in 2017 describes salty tastes. Below is the Ocearch, the first vessel Jefferson’s used to make their ocean-style bourbon.

A test: Why not take the investigation a step further, and place the barrels on deck, subject to the baking sun during the day and cold nights with the added temperature fluctuation benefit of wind chill? That temperature fluctuation causes the casks to expand and contract in a higher variation and more frequently than they would if they were sitting in a stationary rickhouse, under a roof, somewhat protected from the elements and, restricted to a gradual annual weather cycle. In the meantime, place a few from the same batch in the hold, and also keep a few at the rickhouse. Blind taste all three together in random sampling to check for salinity and also measure the salinity and check it against human detection levels and identification levels. The aging part of the experiment is believable and true. It’s the salty part of the experiment that needs proof, and if it can be substantiated, did the salt migrate into the barrel from the salty sea air? Highly unlikely,

Reviews on the Islay and Island scotches and Jefferson’s Ocean bourbon tend to be written by those who feel a reference to the briny seaweed, and salty flavors is obligatory in notes due to their proximity to the sea. They know in advance what they are tasting, and they fear that omitting the ocean flavors would be considered an unforgivable oversight by the public and would result in a loss of credibility if not addressed. They think it ought to be there. If there were nearby sewage treatment plants or fertilizer factories, how would they describe the flavors of the spirit?

Additionally, detecting the salt and brine of the sea is a great opportunity to enhance the taster’s mystique, especially where other evaluators and review writers don’t detect that subtlety in the same spirit. It is more about one-upmanship, “My nose is better than yours.”

Prove it through unbiased testing. Taste these spirits in flights with inland spirits, blind, to convince a scientist. Until salty show up in professional sensory evaluations, salty taste is simply not a proven character of spirits made or aged near the sea.

Another test: Perform true double-blind tastings of known seacoast distilled spirits to validate. Tasting participants should not know there are any coastal or island whiskeys in their samples (which should have published notes from the romantics to describe their saltiness to qualify for inclusion). In addition, the participants should be asked in a subsequent tasting of the same whiskeys in a different order to be on the lookout for any particularly salty tastes. The answers from several trials to ensure high confidence should resolve the issue once and for all. Until then, the coastal character is a myth of the romantics.

If salt, saline, or brine intensity can truly be detected, the next questions are; “Where did it come from?” and, “Are the distillers adding salt or saline to the spirit before barreling or after aging to create differentiation and inadvertently perpetuating the myth? Check out this interesting home experiment at this URL:

Takeaway: Until scientifically proven otherwise, salt in coastally made spirits due to the salty sea air, is still a myth. Some whiskeys may taste saltier than others, but the real question is how it gets there. Distilling near the coast has not yet been proven as a natural source of salt in spirits, and salt may be detected in other spirits not distilled in coastal areas, so as a characteristic geographic attribute, sourced through the sea air, the argument doesn’t hold water. Adding salt to a whiskey can reduce bitterness. More questions to ask. “Do the distillers know this, and is it a dark distillers’ practice? What other spirits distilled near the coastlines (besides whiskey) have a salty taste? Is it a character of geographic distillery location?”

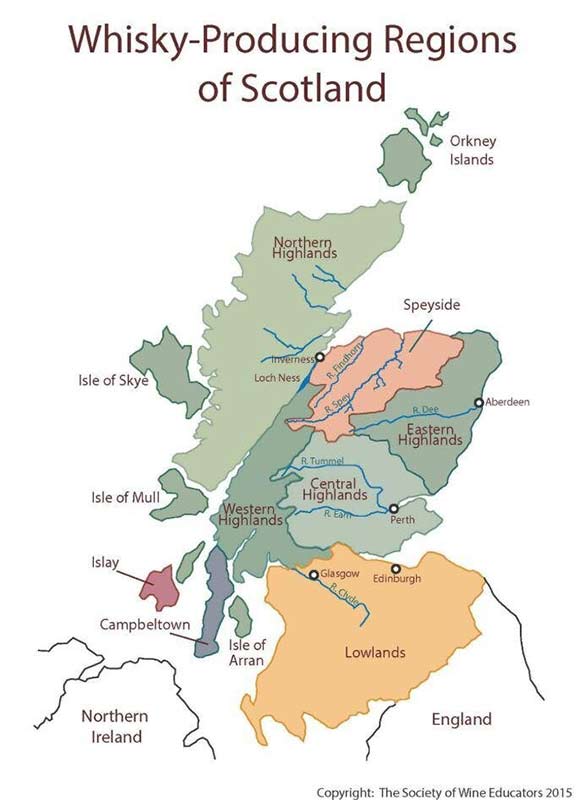

Myth #3 – Regional characteristics of scotch: Scotch lovers, in their zeal for embellishing their favorite spirits, tend to create an overall regional flavor profile for Highland, Lowland, Speyside, Campbeltown, and Islay scotch. For several reasons, dumping all the distilleries of a region together by flavors, mouthfeels, and taste to create a regional template or format of character is not a fair idea, especially for those who choose a different style of distilling. Oversimplifying and generalizing are the wrong approaches.

- Water is a key difference between distilleries, and pH and minerality vary from stream to stream to spring to lake, differences in these qualities are significant reasons for a wide range of mouth-feel variations between scotches. However, the minerality and pH of water do not change abruptly when arbitrary and sometimes politically established geographic borders are crossed.

- Distillers’ practices may be similar in small areas, with some distillers within a region using many of the same practices, and collaboration in sharing techniques with their neighbor distillers, but it is certainly not region-wide or border-specific.

- Malt differences create different flavors as well, however, malt is not necessarily regional, and few malting houses are on the same site as the distillery. As a result, sourcing is more often decided upon by price and availability rather than flavor characteristics. Malt grown in the lowlands could well be sold to a highland distillery. Would that scotch then exhibit the regional highland flavor?

- The supposition that different regions have different characteristics such as the commonly used full-bodied whiskies of the highlands and the light-bodied characteristics of lowlands is a notion that does not belong in objective evaluation. These characteristics are not the property of any district or region, and any distiller can choose to make any style he chooses, some single distilleries making several styles at the same distillery, regardless of distillery location.

Perhaps there is some human urge or trait of a few to classify regardless of fact. If one must overthink or artificially bundle spirits by region, first research, and make a solid contribution by establishing regional boundaries by water characteristics. Hard water ions, like Calcium, Iron, and Magnesium, and pH measurements affect mouthfeel and may (or may not) contribute to some sort of regionality by intensity (concentration). Assigning aroma and flavor characteristics to a geographic region is ridiculous as it excludes so many distillers in the region whose products are atypical, and that makes all regional charts and flavor wheels a poor source of information. The only way this argument can prevail is to convince the passionate, consummate scotch drinkers it is unfair, or until it fades with the generations as science is finally accepted.

There are simply too many exceptions to fall into the trap of assigning a table of regional characteristics to that region’s products. Let science do the work, and reconstruct it with reason and forethought considering natural resources, rather than convenient geographical borders, if it must be done at all. Accurate evaluation is devoid of expectations of which characteristics might be encountered. Predisposed opinions and profile templates simply cloud objectivity and are unfair.

The following chart is included because it also shows the sub-regions of Highland Scotch. Note that the Island scotches are considered to be Highland scotches, making it more difficult to come up with a template of characteristics of Highland scotches.

Myth #4 – Age and price mean quality: This gross misstatement is included here because amateur nosers and tasters are culturally trained to believe older is better, and expensive is better. The truth is on the nose and palate. Blind tastings are a sure way to knock down any preformed opinions about quality as it relates to price and age. The downside to age is that too long in the barrel brings up many flaws which smell and taste bad. Evaluation is always more objective when the evaluator does not know exactly which spirit is being evaluated within a flight of three or four, and retests occur in different orders. Taste first, look at the price and the label later. Simple people believe that more expensive is better, and advertising can be a source of truth and knowledge. As a result, the spirit with the flashiest or most relatable ads wins. Marketers know this.

Myth #5 Single Malts are better than blends: Here again, it is all about snobbery. Learning the particulars of spirits categories is key to comparing them fairly against their peers. We all have different tastes, and some prefer blends far above single malts and don’t know why (if there is a “why”). The same type of snobbery can apply to single-batch bourbons. Take each category for what it is, and learn the characteristic flavors associated with each category. “Better” varies from individual to individual. Evaluators need to understand the characteristics of all spirits and how they are made to judge them properly against their peers.

The information in this presentation is highly controversial and may step on a few toes, but the myth is not worth believing until it can be proven true. Always be open to positive proof, especially if has a scientific rationale and experimental validation. Many of these myths pertain to scotch, but the lessons learned stand for all spirits. Using a scientifically designed glass is the key to understanding why many of these myths exist, as most of them are the result of an unconditional acceptance of the non-functional tulip. Our research can point you in the right direction, and independent research validates our findings. See how we arrived at the final design for NEAT.

In our next presentation, we will discuss the controversial subject of Adding Water to Spirits.