When You Add Water to Spirits (Almost Never)

Much of this presentation contains information from an “adding water” article we published on Linked-in on February 10, 2016. To date the Linked-in article has 59,818 views.

Many whisk(e)y drinkers add a little water to their spirit when tasting, some add a lot of water, and some get very peculiar about counting drops with an eyedropper and using vials of the exact same stream water used in the distillation and reduction process to maintain pH and minerality. The traditional process of serving absinthe also involves adding water, and ancient civilizations added water to their wine, although for a much different reason.

How did the addition of water ever become a popular idea among straight spirits (whisky) drinkers? Most whiskey drinker noses and palates have been conditioned for decades to drinking whisky from the industry’s preferred and taught iconic badge of straight whisky drinkers, the tulip glass. Assuming that the supported iconic glass was the only suitable choice, those who tasted and evaluated and published tomes of whisky literature and reviews began to realize that certain precautions had to be taken to keep the nose and palate on point for multiple evaluations. What evolved was a standard tasting procedure designed to reduce the numbing effects of strong, concentrated ethanol to avoid fixing the problem by abandoning the iconic tulip shape glass. Over the decades, the following “safeguards” against nose-numbing appeared in the ritual of tasting and evaluating whisky (and other spirits). Those “safeguards” are:

- Wafting the aromas toward the nose with the free hand to acclimate the nose to the strong burn of ethanol (numbing sensors quicker, gradually but avoiding the initial olfactory spike of pungency/pain)

- Approaching the nose with the glass at successively closer positions to the nose while sniffing to acclimate the nose (numbing sensors quicker yet gradually to avoid the pungency/pain)

- Breathe through the nose with the mouth open to reduce inhalation force, and thus reduce the amount of ethanol molecules impinging on the epithelium for a given sniff (dilutes the sample with air from the mouth, inhibiting aroma detection)

- Recommending not to swirl the spirit (swirling promotes quick evaporation of ethanol which numbs the nose)

- Some recommend not to smell the spirit, taste only, and let the retro-nasal do the aroma detecting (much less effective in detecting aromas than combining with ortho-nasal sniffing). The addition of saliva in the mouth dilutes the ethanol palate burn and also reduces olfactory sensor numbing by limiting exposure to the ethanol, however, the olfactory aroma sensation is significantly reduced

- Add a few drops of water to “open up” the spirit

- Most drinkers do not care about the quick ethanol effect, as they do not see or feel the onset of olfactory numbing, and readily adopt the “fixes” to follow the leaders and continue using the iconic tulip glasses

The development and evolution of these procedures, combined with the knowledge that blenders dilute whisky by adding an equal amount of water to save their noses from annihilation during a single blending session, has led to the somewhat widespread practice of straight spirits drinkers purchasing eye droppers to add “just the right amount” of water.

The mystical, laboratory-procedure-appearing, showboating eye-dropper addition of water by brand ambassadors and educators at seminars throughout the industry served to validate the procedure to many drinkers, cementing it as a necessary part of whisky evaluation for many gullible drinkers who do not understand the results of the process, but want to do exactly what the “experts” do. The problem is the “experts” don’t understand it either, or they would most probably not add or water, or at least teach water addition for the correct reasons (read further, there is a right reason to be discussed).

During the long, painful, arduous creation of an involved procedure for tasting, evaluating, and blending whisky, none ever considered that standing by the iconic tulip glass was the origin of the problem and that the effect of ethanol on the olfactory could be assuaged by using an open rim, wide-mouthed glass.

Adopting another glass was out of the question since large, open-rim style glasses are by definition not a tulip glass, and switching to a much different glass design could destroy the hard-won unity and fraternal kinship of whisky drinkers so important to the scotch industry. Rather than create a commercially upsetting “which glass is the right glass” controversy, the alcohol abatement procedures, including the addition of water, appeared to be up to the task of maintaining the status quo and keeping the icon. In unspoken agreement, most of the major players understood the consequences and opted to actively teach the intricacies of how to use the tulip glass properly.

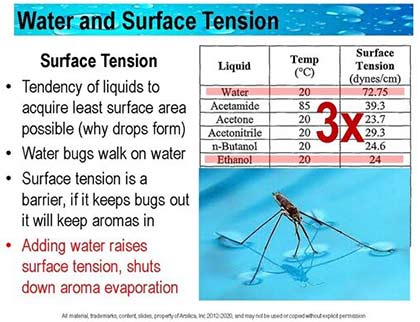

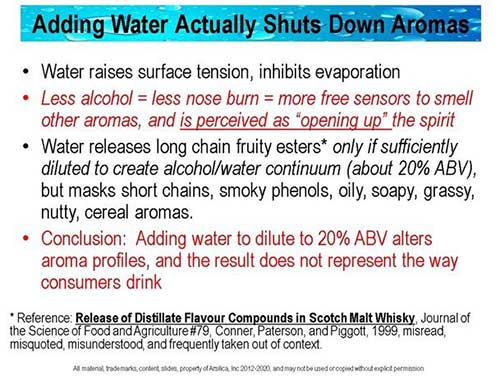

The Science: How powerful is that few drops of water added to your whisky? Water raises the surface tension of a spirit, and inhibits evaporation, not selectively ethanol, but all character aromas as well. However, since nose burn directly from ethanol is somewhat alleviated, the resulting higher degree of comfort in the nasal passages leads the drinker to believe that water “opened up” the spirit when it actually “shut down” the spirit. The perception of pain is gone when water is added, and the erroneous conclusion is that water “opened up” the spirit. The effect is similar to not swirling, as both reduce the evaporation of volatile ethanol (and everything else). The table below shows the difference between the surface tension of ethanol and water. Water has a three times higher surface tension than ethanol.

Not only is there much less evaporation when water is added, but higher surface tension makes it more difficult for the long-chain esters and higher mass molecules which provide more character aromas to be detected. If anything, the evaporation of long-chain character aromas is restricted more by the addition of water than is the nose-numbing ethanol molecule evaporation. At high dilutions to 20% ABV, the process is reversed, as a continuum of water and ethanol releases the esters, but masks other aromas, changing the aroma profile (see exhibit below).

In a previous presentation, we discussed the blenders’ preference to dilute their blending samples to 20% ABV to save their noses during the blending process. Most whisky drinkers do not know that the reduction of a spirit of 40%ABV to 20%ABV requires the addition of water in an amount equal to the amount of spirit being diluted. This is a 50% dilution. In the attempt of the whisky-drinking public to use the same glassware and procedures as the blenders, they have skipped over the significantly high dilution ratio when adding water with an eye dropper to add only a few drops. The higher the ABV of the spirit, the more water would be required to dilute to 20%ABV. If the sample were a 60% ABV spirit, dilution would have to be over 3 ml of water to 1 ml of spirit to achieve 20%ABV. Who drinks it that way? We know of no consumer who adds that much water to their spirit for drinking enjoyment, but it is standard blender practice to save the nose. Sometimes, it just doesn’t make sense to do what the experts do.

The problem with diluting to these levels is that it has been proven that dilution to 20% ABV changes the aroma profile of the spirit, and the blenders are a profile that no one understands except the blenders themselves, since most whisky drinkers who add water, only add a few drops. Further information is available in the journal paper cited in the exhibit below.

Why does the process continue? Blenders want to keep the non-functional tulip to maintain continuity of expression for the industry’s accepted iconic identity badge. The practice raises questions: “What aroma profiles are the blenders working to? How do they resolve that profile to the different profile experienced by the public who drinks the same spirit straight? Why is dilution by the blenders continually ignored in the education of new drinkers? Etc.”

Why should anyone add water to their spirits? For only two reasons; the most important “I like it that way,” and the second most important is, that palate burn makes the spirit unbearable in the mouth for some. A third reason could be a more sensitive nose; however, the sensitive nose issue can be cured by exchanging a tulip glass for an open-rim glass. Otherwise, adding water may solve the olfactory burn issue, but inhibits the sensitive nose experience.

If your reason is “I like it that way,” so be it, but be open to other approaches. If your reason is palate burn, change your evaluation procedure. Nose the spirit first in an open-rim glass, then determine your formula for just how much water will alleviate palate burn, recognizing that when the spirit is introduced into the oral cavity, saliva will quickly begin to dilute the spirit. Taste the sample from a separate glass in which some of the full-strength spirit has been diluted enough to alleviate sharp palate burn. Keep the sample in your preferred nosing glass for reference back to the nose if needed. An alternative is to take satisfactory notes from the nosing glass and then add water to taste, but that eliminates the possibility of returning to the original nosing sample.

The Holy Trinity of Absinthe: Made from herbs, including green anise, Florence fennel, and artemisia absinthium (wormwood) as its namesake ingredient, was invented (according to some sources) by Dr. Pierre Ordinaire, a refugee from the French Revolution who fled to Couvet, Switzerland, and concocted the first absinthe in the late 18th century, later, Pernod opened the first absinthe distillery in Switzerland. Originally widely used as a medicine, absinthe began to acquire a reputation for causing insanity, as many famous artists, poets, and authors are credited with drunken rages of epic proportions (presumably intermixed with fits of creativity), and eventually was denigrated and classified as a psychoactive hallucinogen, banned in the US and much of Europe. These properties have not been proven. A quick appreciation of the colorful history of absinthe is noted in Wikipedia: Absinthe.

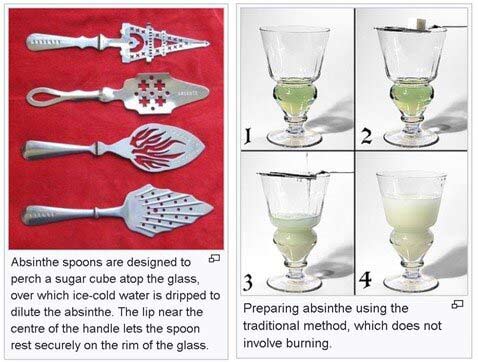

Traditionally, absinthe is prepared for tasting through an involved procedure using a special “reservoir” glass, and an absinthe “spoon” which looks more like a strainer. In the French method, sugar cube is placed on the spoon and it is positioned over the rim area of the reservoir glass which contains 1-part absinthe. Then, 3-5 parts of ice-cold water are poured over the cube to produce a milky white solution as many of the compounds in the absinthe precipitate out of the solution. In the Bohemian method, the sugar cube soaked in ethanol and lit to burn a beautiful ethanol blue flame.

The explanation of adding water to the absinthe (“blossoms out”) is similar to the scotch whisky explanation (“opens up”). Two factors make the over-proof absinthe (45-74% ABV) palatable. Adding 5 parts water reduces the highest ABV absinthe to around 15% ABV, avoiding palate and olfactory burn, and making the drink palatable to anyone who loves anise. Additionally, the ice water drops the temperature to reduce evaporation almost entirely, and the resulting aromas must be picked up in the oral cavity as the tongue warms the temperature enough to provide retro-nasal aromas. Water is a great equalizer for palate burn, but shuts down aromas. Again, the science validates how it works, albeit in a fashion very dissimilar to the traditional, more romantic explanation. The absinthe process makes a harsh, high-ABV liqueur extremely palatable, mostly due to the addition of water. Pics below borrowed from Wikipedia: Absinthe.

Water in Wine: The ancient Greeks and Romans, adults and children drank wine every day, all day from morning to night. Although there was lots of water for baths, irrigation, and sewer, pure, odor-free disease-free water of high enough quality to drink was not always available, and the alcohol in wine provided some purification to make it more drinkable. The problems were drunks and alcoholism. Dilution was extremely important to a well-functioning society and wine was diluted by the Romans as much as 6 parts water to 1 part wine with dependency on the wine’s alcohol as a purification safeguard. Supposedly Jesus diluted his wine with water at the Last Supper. The practice was common. Wine was a gift from the gods, and over-indulgence was frowned upon then as it is now. Close Roman social gatherings were said to be monitored by an appointed Magister Bibendi (the head of the party) who was responsible for mixing the wine with water to control the guests’ behavior, who was probably a formidable personage capable of maintaining control and the decorum of the event. The alcohol content of the wines of the ancients is vague, but some sources say it was as high as 20%. One discovered and preserved, a well-detailed story from the Greeks recalls a party at which the Magister Bibendi uses his powers to turn the party into a drunken orgy after most of the guests have gone home, and the core, heavy drinkers and “party animals” remain to revel well into the next day.

Cask strength spirits: Undiluted, straight from the barrel, whisky, rum, aged tequila, and other aged spirits can exhibit an ABV (alcohol by volume) of 45-70%. The curiosity of the consumer has created a market for spirits bottled at their cask strengths (remember that most spirits are diluted, bottled, and sold at 40% ABV). Many bourbons, whiskies, and rums are now produced and sold at cask strength to a specific market. These spirits present a higher probability of olfactory numbing if evaluated from a tulip glass, and an attending higher level of palate burn regardless of the glass used. Some never seem to get enough of a good thing, and similar to the snobbery that accompanies price vs quality, and single malt vs blends, the snobbery among cask strength aficionados is legendary. An open-mouth glass can eliminate the nose-numbing issue, and the addition of some water can reduce palate burn but defeats the whole idea of drinking cask-strength spirits straight. Many macho purists see changing glasses and adding water as a travesty and abomination. The mentality is similar to the macho “hot pepper syndrome,” the hotter the better, and “I can stand it hotter than you can,” spoken with a reddened face, bulging eyes, and enormous beads of sweat dripping from the forehead.

Water quality and characteristics: Contrary to a few published articles the minerality, bicarbonate content, hard mineral ions, and pH of the base water used in reduction water is hardly, if ever, noted on spirits labels or in distillery websites or profiles. Many third-party companies offer vials of the water from the streams of the distiller, yet the distillers actually may treat the water from their source before the reduction of the cask spirit to the 40% ABV norm. Sneaking around at night dipping buckets into distilleries’ streams for rebottling (yes, they do it) may be all in vain. This of course invalidates the characteristics of any water to be added to assuage palate burn as representative of that which was added for reduction. In other words, you will most likely never know and be unable to approximate the pH and minerality of the water which was used to reduce from cask strength to bottled 40% ABV. Then again, why add water? If using an open-rim glass, palate burn may be a valid reason. Cask-strength spirits can be painful to the palate (whiskey, rum, absinthe, tequila, etc.)

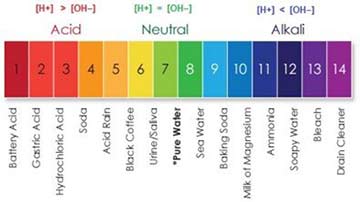

The term pH is used to signify the power of the hydrogen ion, and it is a base 10 logarithmic scale used to define the acidity or basicity of an aqueous solution (water solution). We know that on the pH scale, a 7.0 is neutral. The only true indication from a sensory standpoint, is; if the addition of a particular water changed the mouthfeel of the spirit, it was probably the wrong water to add. Try again using a different water source. A particular bottled water (not distilled) could become your standard additive if you insist on adding at all. Color testing using litmus (a dye extracted from lichens) paper to indicate H+ ions (orange) to HO+ ions (blue) is indicative of acid or basic character. For general reference, here is a simple pH chart with examples of the pH number:

Why should we care? Truthfully, we should not care about the testing or the level of ions, we should concentrate on the mouthfeel of the product as bottled. Slippery and oily feeling can be caused by OH+ ions basicity (tending to blue litmus). If you taste a spirit that feels oily on the inside of your cheeks, it may be from the basicity of the water or glycerides (there is that OH radical again) present in the spirit (a common occurrence). To familiarize yourself with the feel, put some Clorox on your index finger (do not ingest it, it is not a cure for COVID) and rub it against your thumb. That easily translates to a similar mouthfeel of high pH.

To familiarize yourself with the acid feel, squeeze a lemon or lime or place vinegar on your index finger and rub it with your thumb, and notice the austere absence of oiliness as the H+ ion acidity (tending to orange litmus) cuts through the natural skin oils which leave fingerprints and presents a higher frictional resistance to movement. That is one form of astringency that occurs from acidity in mouthfeel. The acidity of the final product is common in tequilas, cognacs, and single malt scotches, and therein lies a potential for adulteration. Many distillers know this and add small amounts of citric acid (or?) to mask post-distillation sugar addition and/or cover up sloppy tail cuts. Some laws specifically allow small amounts of additives including generous maximum citric acid content.

Many wines that do not have enough acidity are characterized as “flabby,” no doubt due to the “fat” and slick, oily feel of abundant OH+ ions. Balance in wine occurs when tannins, acidity, and fruit are present in such quantities that no one attribute appears to be stronger than the other two. Balance is not widely recognized as a characteristic of spirits, and perhaps, if used at all, should refer to neutral or a 7.0 pH, where neither acidity nor basicity variance from your experienced norm as an evaluator can be determined.

Hard water ions typically come naturally from the water source and consist of calcium, iron, or magnesium present in carbonates from limestone, and gypsum. Permanent hardness cannot be removed by boiling water, and comes from calcium or magnesium sulfates or chlorides, but can be removed by ion exchange (resin-based or salt-based water softener equipment). Water softening is a science unto itself, and the important issue to an evaluator is that one never, or hardly ever, knows if or how the water has been conditioned to change the mouthfeel, presenting the dilemma of matching dilution water to reduction water nearly impossible. What are the distilleries doing? As a rule, they are not going to tell you.

Metallic taste can be caused by low pH or trace minerals in the water source and could be dangerous if tasted in ordinary tap water. If the water is from your water source in addition to the spirit, testing should be performed to verify the metals are harmless. Minerality and pH work hand in hand to present a specific mouthfeel. Understanding the characteristics of reduction water is important to the final evaluation and rating of the spirit, and oiliness or austerity is much more of a personal choice, but should be stated in the evaluation notes. Learn design factors that affect tasting perception

Takeaway 1: Do whatever pleases you in regards to adding water, just understand the true reasons why you do it. Lean toward the science if at all possible, as it will enable more conversation and communication with those in the know regarding evaluation. Understanding and teaching are the key to resolving discussion disputes and combatting ignorance.

Takeaway 2: Know and understand those characteristics of spirit reduction water added at the distillery which causes certain mouthfeels. Avoid adding water to spirits before olfactory evaluation to avoid shutting down aroma evaporation from the spirit. Add water to assuage palate burn or pain. Use open-mouth glassware to evaluate spirits to avoid olfactory numbness or pain from concentrated ethanol. If you must add water for other reasons, remember that distilled water has no minerality and will dilute the mouth-feel character of the spirit you are evaluating. Therefore, add water you know is more neutral, around 7 pH, with some minerality. Try several bottled brands, and use whichever appears to influence mouth-feel the least. Reduction water added by the distillery is what it is, a part of the total spirit flavor package, and difficult to match. Getting obsessive about pH and minerality when adding only a few drops is splitting hairs unnecessarily, and displays an uninformed snobbery that the industry and consumer can do without.

In the next presentation, we will discuss gender equity (not equality) in spirits evaluation.