Effective nosing, tasting, and evaluation is dependent on the accuracy of descriptors in written and oral communication. Comments and tasting notes become much more useful when evaluators and those who read the evaluator’s notes can “visualize” flavors in a similar perception. Careful use of descriptors is key to maintaining the commonality of definitions and conveying useful information.

Smelling and identifying aromas is not as simple as it seems. It is multi-dimensional because the olfactory is closely linked to memory. Scents and aromas activate the limbic system, which not only detects and processes smells but also regulates emotion and memory.

We smell a raspberry. On its way to the memory bank (olfactory cortex) the impulse from the olfactory bulb is picked up by the hippocampus, part of the brain which is vital to recently acquired information storage, emotion and learning, and also the amygdala, important to eating and drinking. The impulse proceeds to the olfactory cortex for recognition, and the realization “Aha, its raspberries” is recognized with memories of recent visualizations of the most prominent scenario(s) from the personal library of raspberry experiences. That smell/visual/emotional memory may instigate a smile and instant salivation in anticipation of tasting the raspberry,

Other reactions occur with the smell of ipecac or rotting fish, which may instigate vomiting and fear or anger. Smell isn’t simply detection and recognition. Smell invokes a summary of the visual and emotional experiences that occurred during detection, and they are inseparable. Perhaps that link is our innate survival mechanism which prevents us from ingesting poison (the flies dropped dead when they came in contact with that smelly liquid, so I wouldn’t touch it) or avoiding a particular odor associated with an unpleasant event (upset stomach) or motivates us to seek satisfaction from detecting a particular smell (baking, fresh berries, barbecue).

Keep in mind that many processes occur simultaneously in the subconscious “back room” of the brain, and it is vastly different for each of us. Reaching agreement on which descriptors should be used to profile a wine or spirit can be a major undertaking when each individual visualizes and emotionalizes an aroma differently and each has a limited (and different) learned vocabulary to describe aromas, feelings, and visualizations. Evaluators with small vocabularies have nothing to say or are at a loss to describe the experience.

Understanding the link between emotion and aroma is a major step to understanding why others describe the same food, spirit, or wine differently. They didn’t describe it wrong. They are right, as are all individual perceptions, which personally belong to each of us. Disagreement in flavor and aromas is usually a misunderstanding of terms and requires deeper discussion to reach an agreement.

Connotation and Denotation: The same word can mean two entirely different things.

- Denotation is the literal, direct, or specific meaning of a word, as found in a dictionary

- Connotation is an implied meaning separate from the definition, that embodies a cultural or emotional association

Connotations can carry immediate positive or negative reactions. For example, the word cheap implies a bargain (positive, right?) but the connotation is just the opposite, bordering on worthless (negative).

- Denotation: Inexpensive, costs less than other comparables

- Connotation: Not worth the cost at any price, cheaply made, poor value. Public misuse of the word cheap over the years has been tagged cheap with a negative connotation and disdain.

Connotations may be similar in general for a large portion of the population, as in the cheap example, created by some event or news, sarcasm, or viral meme; for example, “you are really bad,” meaning “I admire your outrageousness (which is good).” Personally, connotations are created through individual development, reiteration, and linked memories of events that may have steered the individual’s connotation of a word far away from its known denotation (definition) and understanding of others. Much disagreement and “snobbishness” can be sourced to individual differences in connotation which imply an elitist attitude.

Evaluations improve and become more universal, useful information suitable for use by others when all parties rely on and use denotations in conversation and note-writing. The “craft” of evaluation and diagnostics by fallible humans has a protection or safeguard intended to preserve it as meaningful, useful information. It is self-governing, and evaluators must (1) strive to seek truth in the description, (2) recognize that the principle of truth as a group mentality is critically important to the craft, and (3) that truth must be maintained during discussions, when creating notes and reviews, and when used in casual conversational comments.

One word commonly misused when applied as a descriptor to spirits tastings and evaluations is the adjective smooth.

- Denotation: No one knows exactly what taste, flavor, aroma, or mouth-feel characteristics can be defined by smooth. Common denotations (definitions) of smooth are; having an even and regular surface, free of projections, unwrinkled, featureless; or motion without jerkiness, or charming, unctuous, urbane, sophisticated, polished, ingratiating, none relating to flavor or aroma.

- Connotation: Varied; inconsequential, uneventful, simple, planar, none related to flavor or aroma, but unfortunately, to the more experienced evaluators, those who use smooth to describe wine or spirits brand themselves as amateurs who don’t know proper descriptors and the connotation points to the ignorance of the one who dares to utter the word smooth.

This connotation will not go away, so it may be smart to remove it smoothly from the vocabulary to avoid future possible embarrassment, deserved or not. Someone will eventually call it out, probably in public, and it is not a defensible position.

Confusing Definition of Terms: Definitions are the soul of evaluation. A common confusion in spirits and wine evaluation occurs between the terms taste, aroma, and flavor.

- Taste occurs only on the tongue and there are only five (sweet, sour, salty, bitter, umami) nothing more, nothing less.

- Aroma occurs only in the olfactory cavity (ortho-nasally or retro-nasally) and there are thousands of aromas

- The flavor is a combination of aroma (90%), taste (5%) and mouthfeel (5%) generally

- Mouthfeel is a chemosensory characteristic that may be any one of hundreds, perceivable by humans, such as metallic, oily, minty, acidic, hot, cold, or many other descriptors not classified as aromas or tastes

The most common mistake is using taste to describe flavor. As mentioned previously, we do not taste raspberries, we smell raspberries, taste sweet, and our mouth detects the tiny hairs and the slightly acidic character. The total information packet of all signals is a single flavor perception sent to the brain (olfactory cortex) to search for an identification match in the flavor database.

Cultural Differences: Different cultures have different definitions of taste, and the Occidental (western, European, North American) definition of taste (sweet, sour, salty, bitter, and umami only) is generally used to describe the spirits of those geographic origins. Many mouthfeel characteristics in Western cultures are classified as tastes in other cultures. Medical and sensory science for the most part has adopted the Western definitions of taste and aroma, but one should withhold criticism of evaluators whose basic definitions of taste are culturally dissimilar. The Chinese regard spiciness or pungency as a basic taste. Pungency from ethanol, capsaicin, piperine, gingerol, and allyl isothiocyanate (horseradish) are examples of chemesthesis, which is not considered taste in the occidental technical sense, but are taste to Southeast Asian, African, Hungarian, Mexican, and Peruvian cultures (to name only a few).

When tasting international spirits, consider the words that are used to describe spirit characteristics within the culture surrounding the spirit. These words vary widely from Western culture by country. Sake, Okolehao, and Baiju are just a few popular beverages that have their descriptive terms used by their native evaluators. Cultural differences may seem inconsequential, but awareness is a solid asset when reading international tasting notes or having discussions with evaluators from other countries.

Experiential memory plays an important part in our recollection of smell: As discussed, when describing aromas and flavors, we also conjure up emotional memories that we associate with our word descriptors. Grandma’s apple pie has a positive emotional connotation for those who recall it;

… the pervasive smell of baked apple, caramelized sugar, nutmeg, and cinnamon, the warmth, and pleasant, loving looks shared around the table among all seated as dessert was served near the close of that rare, but indelibly perfect day of joy and family, accompanied by Grandma’s radiant smile, exuding confidence in anticipated praise of her special day’s creation, her delicate hand lovingly and reassuringly patting your shoulder as you fork that first bite into your mouth, slathered by the fragrant aromas and coolness of the homemade French vanilla ice cream placed next to it on the saucer – the very same ice cream to which you devoted an hour of feeding salt and ice to the mixer and hand cranking feverishly until your arm was stiff and racked with pain…and so forth. Inextricably, the complexities work together to create a memory like no one else’s; the perception of that moment in time gets better with each recall. Yes, we do that. We can’t stop it,

When discussing the attributes of the same apple pie recipe (or moonshine expression) shared with Bill, who lives next door, Bill says:

…I am not a fan the smell reminds me of the time a huge cockroach crawled out from its hiding place under the pie causing screams and pandemonium, and the table was turned over by Grandpa when he spied the ‘roach…

This connotation is Bill’s impression of the smell, and it could take on nightmarish proportions if combined with his intense hatred of insects and associated germophobia, and more so if Grandpa died when his head hit the corner of the cast-iron stove as he turned over the table.

The examples are extreme to emphasize the point: Each person has a different experiential memory regarding the smell of Grandma’s apple pie, some not so pleasant. Personal perceptions of descriptors are different due to individual differences in experiential memory, and emotional state as the memories were formed. We truly have no idea what the other person may be thinking or seeing until the conversation develops to a deeper level.

Furthermore, we embellish the memory with every recall as we internalize new feelings or thoughts about the experience, we add the red sunset through the window in one recall, and sissy’s engagement announcement at the table at the next recall, and so on. We frequently turn visualizations from negative to positive, or vice-versa. Bill, a year later, “Now that I think about it, since Grandma died, I realize the flavor and aromas of that wonderful pie were much more meaningful to me than an insignificant cockroach. Amazingly, after Grandpa died, Grandma’s apple pies just seemed to get better and better.” Our visualization of memories triggered by aromas and scents can transform into whatever we wish, and we absolutely will transform them. Yes, we do that. We can’t stop it.

In addition, repetitious tasting and reiterations burn subtle characteristics into memory for accurate identification. Ask anyone who has attended regional blind tastings as a spectator with “hands-on” vintners of Bordeaux, (or any other region) and watched them identify their wines poured from thirty or more random brown bag-covered, foil-less bottles, correctly naming vintages again and again, and also identifying wines from their next-door neighbors’ vineyards. Wonderment, excitement, loud cheers, and clapping fill the room. It is not magic, although it appears so. It is experience, reiteration, keen memory development, and focused concentration during evaluation. It is the magnificent realization of human capabilities. It is Zen. It may be what you want to achieve lifelong, so consider it.

Misleading descriptions and Fantasy: Artful prose may make for captivating reading when describing wine, spirits, and food, but there’s little to gain for the serious evaluator. Many bloggers and self-styled raters and evaluators use their own published notes to attempt to prove or reinforce their knowledge to others. They flower notes with environmental, emotional, and impressionistic adjectives attempting to instill appreciation or adoration from the reader, and desperately hoping to build a large, loyal following. At this point, the wording and descriptive adjectives provide a conjured visualization that is different for each reader’s perception and contains no useful information. Visualizations of others, real or fantastical are difficult to accept unless lived vicariously or personally experienced.

Many descriptions are so insidious that the chance of identifying with a reader of the same experience is remote, and therefore they lose credibility as useful information. A few phrases can illustrate the point well:

- “…the sweet aroma of overripe wild mangos of the west coast of Kauai on a breezy, overcast day…”

- “…musty, fungal, ancient smell of the centuries-old, damp, medieval wine cellar…”

- “…earthy aroma of Romanee-Conti vineyards just after a light rainy drizzle…”

These descriptions mean nothing if not personally experienced, and for those who have not, they conjure dreamy projections and suppositional fantasy rather than convey useful information; proof positive that flowery evaluators should give up writing wine and spirits evaluations and concentrate on novels. These authors most certainly are not as interested in conveying useful information to you as they are obsessed with their flowery prose and eagerness to display carefully constructed panache. Stay away, don’t adopt the philosophies of fakers to the craft. If you are a serious evaluator, these are not your people, they can live without you to slither another day for a different audience.

Had the previous Grandma’s apple pie visualizations been included as part of a spirits review, the result would have been instantaneous nausea from a solid evaluator. That kind of stuff should stay in memories, where they belong, or in the products of Hemingway and screenwriters like Clark, Shepherd, and Brown (A Christmas Story). Since they invoke personal fantasy when read, they do not belong in spirits reviews where denotative information is important to believability and relevance.

Dangerous use of simile: Another mistake in describing spirits and wines is getting carried away in analogies of tasting to other non-related experiences, such as riding a motorcycle, skydiving, swimming with sharks, pirates stealing rum, spectacular macho feats of athletic prowess (all have been used), and more critically sexual experiences or sexist innuendos. The latter has recently led to a great loss of respect for a prominent whisky evaluator, icon, and author. Stay on point, and never get full of yourself.

Recall memories have a significant commercial impact. These memories may be exactly why we prefer and purchase a particular wine or spirit. The lemon aromas and flavor of a Dalwhinney scotch, and the raspberry notes of the wines of Mercurey in Burgundy are legendary for invoking purchasing decisions solely to capture their desirable flavor characteristics.

Takeaway #1 – Objectivity and Emotion: We each have a different recollection of particular smells and flavors. KISS (keep it simple, stupid) should be the mantra of evaluation for novices and masters alike. Look for flavors and aromas per se, don’t mix aesthetic, unrelatable phrases and similes with evaluation notes. Unchecked emotions cloud objectivity, be critical and screen them for their effect. After performing the more procedural, unbiased flavor and aroma descriptive diagnostics, there will be time for deep appreciation, savoring, and memory association. Be cognizant, and note both pleasing attributes and offensive, detrimental flavors and aromas. Determination, focus, and conscious application of these principles will sharpen the ability to identify aromas and flavors and relate useful information to others. Always consider your sources and validate them.

Where do we find suitable vocabularies for evaluation? There is no one simple source. Discovery is dependent upon reading, research, and personal investigation. Here are a few suggestions:

- Find and follow trusted and respected professional evaluators, and read their opinions and notes, perhaps while you are tasting the same wine or spirit they are evaluating. Read their websites and friend them. An evaluator or blogger’s fame is not necessarily indicative of honesty, forthrightness, and accuracy. Find mentors who match your altruism

- Stay away from vineyard and distillery website descriptions when looking for characteristics, as they are mostly overblown with snobbishness, novelistic descriptions, “come hither” curb appeal, commercial prurient interest, and little objectivity. Many hire professional writers to embellish what should have been straightforward information regarding product characteristics.

- There are plenty of books written by objective authors who present realistic descriptions. You have to find them.

- Flavor wheels can be a good source of vocabulary and many are put together objectively. Many, however, do not include offensive or negative aromas and flavors. Download or purchase more than one (to appreciate the organization of the presentation) of these wheels, and use them as a reference when evaluating. Compare personal notes with those of experts and pull together an overall, bigger picture of how others describe spirits, including similarities and differences.

- Group tastings and interactive discussions at spirits and wine club meetings, liquor store demonstrations, spirits seminars, and other group gatherings are an important part of developing a vocabulary. Discovering and friending people educated in the craft is your key resource to understanding the subtle nuances of evaluation. Distillers and vintners should also be on the “must-know” list. Don’t be afraid to ask questions to clarify thoughts and agreements or disagreements.

- One can easily become a snob, but it is not worth instilling a negative reaction and the possible loss of friendship of even one person who sees through the ruse and identifies it as snobby, or worse, dishonest. People talk, and negative personality impressions spread like wildfire. What your readers think of you as an evaluator can be your key to success or downfall.

Aroma (or Flavor) wheels are an important source of vocabulary and descriptors: Innocuous at first glance, there are pitfalls to relying on flavor wheels alone when evaluating spirits. Remember they are two-dimensional and space limited, and so they are rarely complete. Choose carefully, and become intimately familiar with your choices, especially understanding those terms that you may not recognize. Some wheels (or descriptors) may have been invented by those who would sway evaluation, and some may have been invented by exuberant neophytes who do not have a solid or well-versed tasting background.

In addition, some wheels may group and sub-group aromas in a manner that seems illogical, and continuity of thought and placement of groups is easily lost as one travels around the wheel. If using a wheel, at least understand that there may be categories missing, and designer intent may have led to the omission of disagreeable aromas important to objectivity. More aroma wheels are better than only one. Google Images has many to choose from for many different spirit categories, these are random examples, not recommendations.

Some beginners pick out a few dominant flavors and immediately get a feeling of accomplishment for a job well done, completely ignoring other subtleties. When that happens, it is just a feel-good game that delivers a small, immediate, fleeting satisfaction disguised as an accomplishment, and will never meet the objective of completely defining the profile of the spirit.

When writing evaluation notes, never rate a spirit unless you can enumerate the reasons it did not achieve the perfection of 100 (if that is max on your scale, also, 20 may be sufficient according to Jancis Robinson). The con (against) part of the evaluation experience is as important as the pro (good). Something is not quite right when evaluation notes do not include both sides, and it could be an indication that the evaluation was bought or planted. ATTRIBUTES – DETRIMENTS = RATING.

The professional sensory science approach: In the previous presentation we discussed a professional research study. Before each evaluation by spirit, the tasting panels convened to establish a usable lexicon vocabulary upon which all could agree. Development of the lexicon was a single day of training and all sensory attributes were measured on a 150-point scale from “none” to “strong.” This scale was picked vs another arbitrary number, say 100, because a single degree of difference in the higher number of 150 represented a larger measurable and notable difference for the panel.

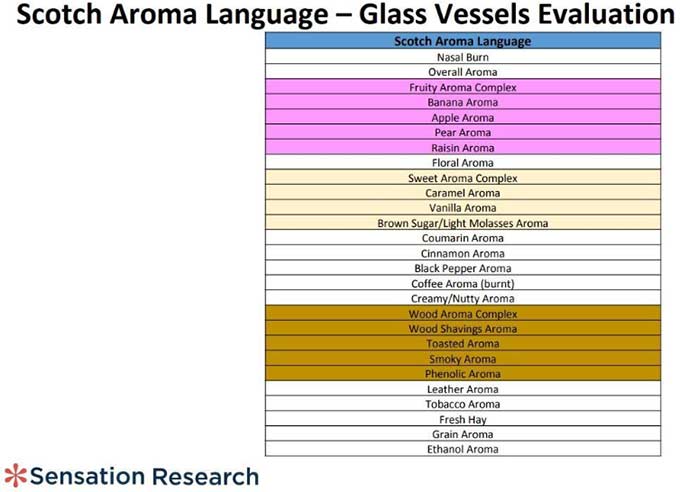

Establishing the lexicon is common practice in professional sensory studies, and enhances repeatability and statistical confidence levels in significantly detectable aromas. Focusing on the major aromas present in the spirit and discarding outlier aromas (detected by only one of the 20 panelists), focuses the study on the major differences. A sample vocabulary for the specific scotch used in the evaluation is shown below to illustrate the balance between simplicity and complexity (logical groups and their constituents). Lexicons of the other spirits, tequila, and cognac, are included in the original study.

Note the differences and similarities between words on the scotch flavor wheels and the professional study. We cannot emphasize enough how important familiarity with standard terminology is to aroma and flavor identification, particularly the nuances characteristic of each type of spirit. There is no single source of information on the subject, and one must self-educate by reading and comparing to achieve a high degree of competency in evaluation. A good evaluator knows what typical aromas and flavors represent a spirit category (bourbon, gin, rum), or type (single barrel, small batch, blend).

What if the burnt coffee aroma above created a discussion, “It smells like burnt Maxwell House,” and the dissension is “No, it smells like burnt freshly brewed Starbuck’s Italian Roast #22.” Irresolvable, because not more than one person could have enough data or recollection of burned coffee experiences to differentiate the origin. Lexicons substantiate detectable aromas to build confidence in the measurement of their intensity.

Since it is nearly impossible for a single evaluator to establish a complete vocabulary on his/her own for each spirit, it is useful to see the simplicity of aromas and flavors at the professional level and to know that to qualify for the vocabulary list, there must be an agreement of multiple individual evaluators. For the level of usefulness necessary to make informed personal buying decisions, understanding the complexity of aromas and flavors and working towards identifying as many of them as possible is crucial information, is significance readily apparent when finally arriving at the final purchasing decision question, “Do I like it enough to pay the price?”

Takeaway #2 – Interactive Participation: There are no shortcuts to developing excellence at evaluation, and knowing what you and others are talking about is the key to establishing depth, understanding, and truth in the evaluation process. If you are serious, don’t be the bystander in the group tasting whose first word is “smooth.” Much more must be said, learn to describe. actively participate in discussions and debates with others over evaluating whatever whiskey they are presenting at the liquor store on Saturday morning. If you don’t jump into these discussions with strangers and friends, you will never know how others value your opinions, and you will never develop your own valuable opinions. Search and discover informative reference materials to jump-start an evaluation education. Ask friends who know, or find those who know and make them friends. Search and find, use or lose. Success is up to you, and how much you desire to perfect your smell-abilities.

Takeaway #3 – Develop Your Descriptors: Whether you are interested in one spirit or many, learn the categories of your spirit(s) well, and create your list of characteristic taste and aroma descriptors. Write them down, and develop your tasting sheet and rating system. Once you have a format, use it in conjunction with the same procedure for every evaluation. Put your descriptors on your evaluation sheet. You will enhance your knowledge, buy better, and show others how to appreciate.

Takeaway #4 – Definition of Evaluation: Evaluation is a craft, a mindset, and a science. Evaluation and diagnostics must have an objective to provide honest information in a universal language with commonly understood meanings. Evaluation is a craft and a skill, because it is all about the Zen of building the mental library, perfecting detectability, focusing experiential memory, knowledge of what went into the creation of the expression, personal awareness of self, and openness with others, and it will improve with practice. Evaluation is supported by a solid base of scientific knowledge of physics, chemistry, biology, and psychology, the subjective ingredient is the evaluator, YOU, and the subjective must become objective. Be better or be best.